Date: 22 August 2006

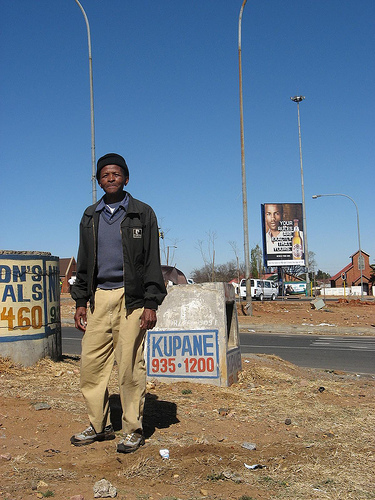

Route Guide: Patrick Lephunya, Regional Director of Soweto

Facilitator: Ali Hlongwane (Curator HPMM)

Documenter: Ismail Farouk

Observers: Oupa Molota (June 16 Foundation),

Angel David Nieves, PHD. (Director Graduate Research & Training, Consortium on Race, Gender, and Ethnicity at Maryland University)

On the 22nd of August 2006, our research team retraced the Naledi High School Route under the direction of Patrick Lephunya, the regional director of Soweto.We began our journey at the school where Lephunya described the events of the morning of June 16, âÂÂAt assembly the principal NJK Molope came in and wanted to sing a hymn but students stood up and shouted out, âÂÂAmandla!â and sang âÂÂNkosi Sikelele Afrikaâ instead. The students unfurled banners and plackards before heading off into the streetsâÂÂ.

Figure: Patrick Lephunya (left) describes the morning's events at Naledi High SchoolLephunya showed us the telephone lines outside the principalâÂÂs office which were cut in order to prohibit any calls to the police. Earlier, on the 9th June, two policeman came onto the school grounds to arrest a student. The student in question, Enos Ngutshane was wanted for questioning.

The principal came into our classroom and said, âÂÂhey, mmona (man) it looks like you are in trouble the police are here and they would like to go with youâÂÂ. Then he went back to his office and continued the discussion with the police just to find out what is happening, âÂÂI took my bag instead of going to the principalâÂÂs office I went to the classrooms where the members of the South African Student Movement (SASM) were and said, âÂÂguys IâÂÂm in trouble the police are here to arrest meâÂÂ. So there was a quick discussion and the guys said, âÂÂyou know what donâÂÂt go to the office, you go back to your classroom and give us 10 minutes [Laughs]âÂÂ. So I was looking at my watch exactly 10 minutes the bell went. But it was not natural; it wasnâÂÂt supposed to be ringing at that time. But they had done their work. They had already moved into all the classrooms to say the bell is going to ring and all of us must be at the assembly. So we went to the assembly and students were in one voice âÂÂyou are not going anywhereâÂÂ.

Later, Ngutshane walked in the principalâÂÂs office and said âÂÂthis is the situation it looks like nobody is going to leave the school, including myself [Laughs]âÂÂ. So there was pandemonium in the principalâÂÂs office. As the three of us were still talking, the white policeman, the principal and myself, the other police guy came in and said, âÂÂhey, the car is now on fire outside [Laughs].

The police car was destroyed, burnt and overturned. Unfortunately the students did not cut the telephone line on time and police reinforcements soon arrived.

(Extract from an interview with Enos Ngutshane)

After, a brief inspection of the school grounds, and the memorial to those who lost their lives in a bus tragedy in Mozambique in 1974, our group set off in a hired mini bus.

Contrary to popular belief, the Naledi High School Route does not make a beeline to Morris Isaacson School as illustrated by the proposed paving route on the Johannesburg Roads Agency map., The Naledi route remains highly contested. However, the initial stages of the route shown to us by Lephunya, is corroborated by Harry Mashabela in his book, âÂÂA People on the BoilâÂÂ. The book contains a very detailed description of the initial stages of the Naledi High School Route.

Figure: Batswana High School

Our first destination was Batswana Junior Secondary School, which is located close to Naledi High School in a South Eastern direction. Today, Batswana Junior Secondary School is known as Thabo Secondary School. Lephunya described how students from the school gathered at the small gate as they waited for the Naledi group to arrive before heading off to Thomas Mofolo High School.

Figure: Thomas Mofolo High School

At Thomas Mofolo Senior Secondary School, a further 500 students waited to merge with the Naledi group. Our journey continued down Mpetslane Street where Lephunya pointed his motherâÂÂs house out. On the morning of the march Lephunya stopped here to drop his school books off before continuing with the march. He also added that there were no incidents at this point of the march.

Figure: Tladi Secondary School

Lephunya directed the minibus right and then left onto Legwale Street before turning left onto Thamagane Street where more students from Tladi Secondary School joined the march. We meandered through tiny unnamed residential streets, and a few sharp turns later we found ourselves back on the main road, Masiane Street. Our next stop was Moletsane High School where students asked us to photograph them in front of the school. We continued on Masiane Street and turned right into Mphahlele Street where we stopped outside Mphahlele High School.

Figure: Moletsane High School

The next part of the route is where the greatest contestation lies. The plan on the day was to merge with students from Morris Isaacson High School and this is supported by Harry MashabelaâÂÂs book, which describes the scene when the Naledi group arrived at Morris Isaacson High School to find the school deserted with a sign at the gate which read, âÂÂNo SBâÂÂs â Trespassers Beware!âÂÂ. LephunyaâÂÂs route, however, does not include Morris Isaacson High School, rather it meanders through the âÂÂbig circleâÂÂ, at Letabe Street in Central Western Jabavu, east of Morris Isaacson High.

An explanation for the contestation can be found in the fact that not all students followed the same path. While the majority of students may have taken the path described by Lephunya, it is possible that some students from Naledi walked along Makapan Street before turning right into Mputhi Street towards Morris Isaacson High School. This possibility can be explained by the testimony of Solly Mpshe in the book âÂÂJune 16 1976â by Brink and Malungane (2001). Mpshe was a student at Morris Isaacson High School. He relates being forced out of his class and being forced to march despite not knowing what was going on. He says that this occurred during the second period around 09.30am and places responsibility for being forced into marching on students from Naledi High School (Brink and Malungane 2001:39).

LephunyaâÂÂs route continued on Letabe Street in a northerly direction until the street changes name to the Moroko Nancefield Road. We turned left into Mncube Street and continued westwards towards Mahalefele Street. We turned right on Mahalefele Street but instead of turning towards Vilikazi Street, the end point for many other school routes, we continued down towards the Klipspruit River close to the point where Hastings Ndlovu was killed.

Figure: Hastings Ndlovu Shooting Site

We stopped just before the bridge on Kumalo Street. On the other side of the bridge is where police were reported to have congregated. LephunyaâÂÂs version of the Naledi High School route ends here.

Sources:

1. Brink, E. and Malungane, G. (2001): Soweto 16 June 1976, Personal accounts of the Uprisings, Kwela Books, Cape Town.

2. Mashabela, H. (1987): A People on the Boil, Reflections on Soweto, Skotaville, Publishers, Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Labels: Naledi High School Route, School Routes, The Routes